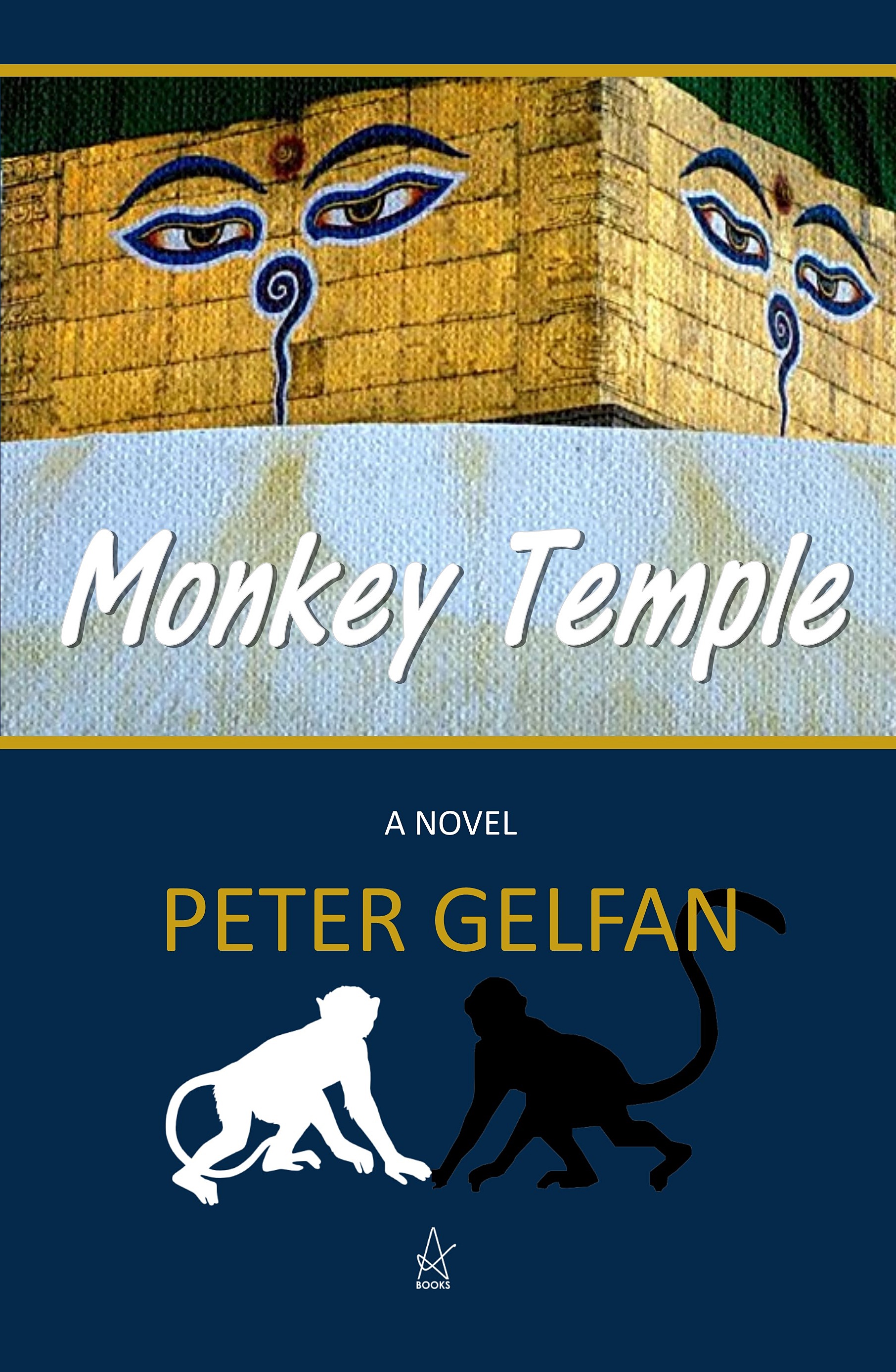

Monkey Temple

Peter Gelfan

Chapter 1

What the hell was Ralston doing here?

I could see him coming a block away. He moved with the same antsy saunter, scanning the landscape, zigzagging slightly when a woman, a ferret on a chain, a pastry shop, then four kids on one bike caught his interest for a moment. But his legs, whose rubbery flexibility used to give him the bounce of a cartoon sailor, now seemed firmly in the jealous grip of his hips. His hair fell to his shoulders in a fringe, gray and wispy now instead of dark and wild. He’d cut it short for a few years in the early ’70s after truckers, construction workers, and clean-cut kids started wearing theirs long, but then he’d let it grow out enough to tie back in a stumpy ponytail.

I stood up from my sidewalk espresso. Ralston caught sight of me. “Jules!” He veered into the café and gave me his usual greeting. “Still mad at me?”

We shook hands and slapped shoulders. His hand felt warm and firm, but the shoulder seemed bonier. I patted it again more gently.

I remembered the ponytail breaking free in the late ’70s, downtown on Broadway, across from Trinity Church, when Ralston had spotted another ponytail, this one coifed and conditioned, swaggering behind a Wall Street type in a perfectly fitted suit carrying a hand-tooled leather briefcase into a waiting limo. Without hesitation, Rals had stripped the rubber band from his hair forever, looped it around the tip of his index finger, pulled it back and shot it at the limo. Ponytail, Esq. hadn’t blinked as it ricocheted off the tinted window six inches in front of his face.

Now, Ralston looked around. “Where are they holding this ghoulish farce?”

I pointed across the street.

He grabbed my cup and chugged the remains of my coffee. “Break a leg.”

Bruno looked better than he had in ages. He’d done it all—read poetry with the beats, meditated with Zen monks in Japan, rode with the Merry Pranksters, studied with Sufis, and, while writing, lived off the land as a hunter-gatherer in the woods of Northern California. The last time I’d seen him, his face had been scarred with fear, loss, disappointment, drugs, disease, and self-excoriation both literal and figurative. Now, many of the lines had smoothed out, and a hint of his once jaunty smile was back. Alone with Bruno for a moment, I laid a hand on his lapel. “See you, old buddy.”

Ritz came over and took my arm. “Jules, you okay, sweetie?” No, although this death was hardly unexpected. Now wasn’t the time to talk about it. I pressed her hand close to my side. Ralston came up behind us and put one hand on my back, the other around Ritz’s waist.

Ritz looked down at Bruno. “Why in God’s name did they want an open casket?” It was a macabre ritual, dating back to the funerals of kings and warlords, when the new order wanted to prove to all comers that the old order was indeed dead. Bruno had been as good as dead for years, and everyone knew it.

“To show everybody it wasn’t AIDS, I bet,” Ralston said. “At least not the ugly kind that wrecks your face.” No one knew exactly what had killed Bruno. I’d tried for years to drag him to a doctor, had even offered to pay the bills, but he always refused. After he was found dead in bed in his apartment, the medical examiner’s office didn’t deem him worthy of a thorough autopsy. Just another lonely old dead guy, spoiled meat in a clean suit.

I glanced over at the new order, Bruno’s daughter and two sons, who looked back at me with tight-lipped suspicion and held their children close by. It wasn’t personal, it seemed they’d always regarded their father’s friends that way, our little crowd anyway. What had Bruno done to deserve such narrow-minded, straitlaced kids? No doubt they wondered what they’d done to deserve a dad like Bruno. Still, their embarrassment as kids and then disdain as adults had torn at him. It came out camouflaged as bitter abstractions in some of his poems—that’s how I read them, anyway—or after a couple of glasses of wine on those rare occasions in the last decade when he’d accepted a dinner invitation. I brushed my fingers across his lapel one last time.

From the doorway, the funeral director caught my eye. I walked to a small podium set up in front of the somber rows of chairs. People took their seats quickly, probably energized by the thought that the ordeal would soon be over. Bruno’s family circled their wagons in the front row to my left as if this were an acrimonious wedding rather than a ragtag funeral, one their father, in his handwritten will, had insisted they hold as a condition to inheriting his small but steady trickle of royalties. The others, in ones, twos, and threes, scattered themselves throughout the rest of the chairs, occasionally exchanging quiet greetings as they reencountered old friends.

One gray-haired old woman—old, Christ, she was probably ten years younger than me—wept openly, perhaps one of Bruno’s ex-lovers. Ralston gathered her in his arms, kissed her forehead, and helped her sit down. Then he settled into a chair next to Ritz at the other end of the front row.

The family would be hoping for a short series of sorrowful platitudes. Too bad. I would do my best to follow the advice I give my clients: have something to say, get to it without a bunch of preliminary bullshit, jump out once you’ve said it, and avoid clichés.

“We’re here to say our goodbyes to our dear friend Bruno,” I said. “He lived an artist’s life—brief moments of creative triumph paid for by years of struggle, rejection, and loneliness.” Bruno’s sour spawn sat in stoic pain.

“Like many of our generation,” I said, “Bruno was an idealist, and idealists gravitate toward four possible fates. One is self-betrayal. We abandon our ideals, or shrink from their challenges, to take a safer, surer path.” Ralston smirked and said something into Ritz’s ear, but her eyes stayed on me, her expression almost worried.

“Two, failure. The world we envisioned—peace, enlightenment, beauty, freedom from oppression—seems further away than ever. Impossible. Laughable. One of the embarrassments of youth.” A few nods from the other guests.

“Three, delusion. We convince ourselves we’ve attained what we set out to, and ignore or explain away the huge pile of evidence to the contrary.” Nary a twitch in the serene smile lounging across the face of Bruce Green, now Sri Green Baba, spiritual and culinary leader of an East Village macrobiotic ashram and trendy restaurant named, of course, Green.

“The fourth fate,” I said, “is to be consumed by our quest. Addiction, jail, exile, insanity.” Bruno’s daughter pulled her small son closer.

I paused for a moment to look over at Bruno. “Bruno was among the lucky idealists. He fell into that fourth category, but his consumption was almost symbiotic, for his poetry sustained him even as it ate him alive. Bruno was a great friend…” I almost added that he was a profoundly compassionate human being, but that was only during those short, infrequent moments when he looked outside himself and beyond the notebook and pen that always seemed to eddy among his restless fingers.

“I could go on for hours.” A gratifying spasm of horror flashed across a son’s face. “But Bruno said it far better.” I pointed across the room to a table holding a stack of small paperbacks—slender volumes of verse, in the parlance. “His poems and lyrics. He hoped you’d all take a book home with you.”

I looked over at the family and waited for them to relent and speak at their father’s funeral. They stared back at me. I wasn’t going to fill the sucking silence for them.

Finally, the elder son said, “We’ve already said our goodbyes.”

Their good riddances, anyway. After a few moments, I nodded to Rosy, fidgeting near the coffee urn, who hit the button on a CD player. The opening chords of Zits Gone Wild’s “Heaven and Hell”—a brief and modest underground hit back in the day, lyrics and piano by Bruno—quavered thinly from the tinny speakers. In unison, Bruno’s progeny closed their eyes in excruciation. I smiled.

“See you around, old friend.” The bittersweet scene and the music I hadn’t heard in years choked me up. “Thank you all for coming.” I faked a cough to the crook of my elbow to hide wiping away a tear and stepped away from the podium.

Mourners exchanged kisses, handshakes, and solemn nods. No one seemed inclined to stay long.

Ralston, his jagged leer now longer in the tooth, again had his arm tight around Ritz’s waist. “What a load of horseshit.”

“What’s a funeral without a little horseshit?” I said. He was right of course. I had no idea where Bruno had gone wrong.

His smirk soured. “Who’s next? You? Me? I hate these fucking things.”

“Why’d you come?” I said. “You couldn’t stand Bruno.”

“Why’s anybody come?”

Ritz pulled my head close to her face, caught my errant tear with a finger, and kissed my neck just below the ear. “Let’s get out of here as soon as we decently can.” She flicked a glance toward Ralston, who, jaw clenched, was scanning the room through narrowed eyes.

That evening, Ralston strode into our apartment, shoved a bottle of champagne into my arms, kissed Ritz’s hand, then turned it over to nuzzle the inside of her slender wrist. Decades ago, I’d told him about that particular erogenous zone of hers, and he’d never forgotten it, had he? He wrapped me in a bear hug. Odd, he didn’t used to be much of a hugger. I hugged him back. He felt almost frail.

“Good to see you, man. Why wait?” I peeled the foil from the champagne cork. “How about some glasses, Ritz?”

Instead, Ralston took Ritz’s hand and pulled her into the living room. “Hey, Jules, I thought you were the kitchen bitch.” Ritz could have grabbed the glasses anyway, but was now sitting across from him, laughing at some whispered joke. At least she’d parried his effort to pull her down next to him on the couch. Her smile and the intensity of her gaze told people they were special to her, a useful trick for anyone to master, but I was sure with her it was genuine. It still made me feel privileged, special among the special. I brought the glasses, sat next to Ralston, and eased the cork out of the bottle with a faint whoosh.

“Still a silent but deadly kind of guy,” he said.

“And you just let ’em rip.”

“Less than a minute,” Ritz said, “and already with the fart jokes.”

Ralston’s trips from Paris always came without advance notice and ended too soon. I’d started making a list of things I wanted to talk to him about, places to take him, new restaurants to try, secrets to pry out of him. I put on my reading glasses and peered at the label. Vintage Taittinger, higher-priced hooch than he usually sprung for. Something was up.

He poured the champagne, handed out the glasses, and then fixed me with his most compelling smile. “To the best of friends.”

Definitely up.

“Best of friends.” We all clinked, and I took a sip. “Sorry to hear about your dad.”

“He was old. It was his time. C’est la vie, c’est la mort.” The who-gives-a-damn spin was no surprise; the lack of a parting shot at the old bastard was.

“Comment ça va Martine?” Ritz said.

“Okay.”

“Just okay? Something wrong?”

“She’s fine. What’s Freddy up to?”

“He got a job with a firm downtown,” I said.

“Environmental law?”

“Still hopes to.” Ralston raised a tousled eyebrow at Ritz. I ducked back into the kitchen.

“Right now they have him on product-liability defense,” she said.

“Jesus, what have you two spawned?”

I came back with olives. “A compulsively neat, sweet-natured, hardworking, sexually naïve—”

“We think.”

“—drug-free—”

“We hope.”

Another raised eyebrow from Ralston. “Hypocrites.”

“—vegetarian lawyer.”

“So much for genetics,” he said.

I nudged his leg with my toe. “So, Martine?”

“We’re calling it quits.”

As when you walk into a glass office high up in a skyscraper and suddenly find yourself looking a thousand feet straight down, I involuntarily swayed backward, away from Ralston and the apparition of life without Ritz.

She lunged forward and grabbed a handful of his shirt. “What are you talking about?”

“I don’t believe it,” I said. “All those years.”

Ritz tightened her grip. “What did you do to her?”

Like a performer basking in applause, Rals smiled and gestured for silence. “Nothing happened. It was just over between us.”

“Things aren’t just over after what, almost forty years?” I said. “Not at our age.”

What was that word they used in Victorian novels to describe the eyes of a tired old man? Rheumy. Ralston looked at me with rheumy eyes and no smile. “You think getting old guarantees anything besides humiliation and death?”

God, it bloody well better. “Of course not, but still.”

“How do Marcel and Françoise feel about it?” Ritz said.

“He’s got a fancy-ass job, she’s married and pregnant. In other words, they both have enough problems of their own not to worry about their parents.”

Ritz sat next to Rals and put a hand on his arm. “How are you?”

He smiled bravely and laid a hand over hers. “I’m fine. We were both in a rut.” He worked his thumb around her wrist and softly caressed that spot on the underside. “Change is good.”

She pulled her hand away. “Change? What change?”

“I wasn’t fooling around, that’s not what this was about.”

“Which?” I asked.

“Which what?”

“You weren’t fooling around, or that’s not what it was about?”

“Neither. Both.” He stood. “Got to go. Just wanted to say hi to you two without a corpse in the room.”

“You’re not staying with us?” Ritz said. “Where’s your suitcase?”

“I brought all my shit with me, so I dumped it with my idiot cousin in Brooklyn.”

Typical Ralston, hunkering down when he was low. “For Christ’s sakes,” I said, “stay with us. Especially now.”

He waggled his eyebrows at Ritz. “Especially now, I better not.”

“What’s your plan?” I said.

A bland smile. “Plan? What plan? There’s no big hurry.” He squinted at me. “Is there?”