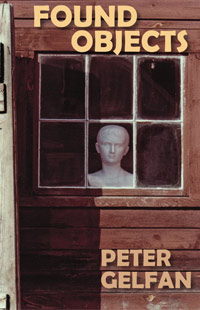

Found Objects

Peter Gelfan

Tonight I’ve watched

The moon and then

the Pleiades

go down

The night is now

half-gone; youth

goes; I am

in bed alone

— Sappho

Chapter One

I am a tidy person, my wife is not. Our lover, Marie, can go either way.

I shelve books after reading them, put tools back in the toolbox, stow my sweaters, coats, and shoes when not wearing them. Erica leaves things lying around: a couple of tomatoes by a potted cactus on the unpolished block of green Vermont marble outside the back door; a bunch of dried flowers tied with a scarf next to a pair of scissors on the windowsill; red mittens in August, one as a bookmark in a cookbook on the living room floor, the other in a photo album next to it.

Because these still lifes force me to wonder how their elements came to rest in the same spot, to try to visualize the sequence of actions that brought them together, to imagine the harmony or dissonance of perceptions, emotions, and ideas that took place while each was being assembled, I consider them works of art. When she needs the space the assemblage occupies or one of its objects, she’s as insouciant in dismantling it as she was in building it, as if her capacity to create and the time in which to do so were endless.

Marie, while neat herself, doesn’t object to other people’s messes, and so gets along well with Erica and me, even acts as a buffer between us.

The kids did watercolors on the porch this morning. From my studio window, I could see eight or ten drying on the grass. The ginger cat sniffed at one of them then stepped back. Even from the second floor, I could easily tell Jasmine’s from Dominic’s. His tended dense, dark, and bottom-heavy—probably his usual war and car-race scenes—and seemed to portend a future full of strife. Jas’s were light, airy, colorful, abstract, and filled my chest with the need to protect her from a world she’d too easily trust.

Marie cleaned up after them when they were finished, not because she’s their mother but because that’s how it usually works out. Barefoot and in shorts, crouching on the grass, she studied each picture before stacking it with the others. The cat batted at the corner of a painting, then leapt onto it when Marie added it to the pile.

As if she felt someone watching her, Marie turned and looked up at me. After a moment, she sorted through the pile and held up a painting for me to see. It was one of Jasmine’s, with light bright colors and lots of space, and wasn’t abstract after all, but a face, with high arching pink eyebrows, purple eyes, a pointed chin, and a wide twisted red smile. The face seemed to be laughing at something, and it was hard to tell if the laugh was friendly or mean. Marie pointed at the picture and then at me. I laughed and made a face, but she might have been right.

Erica cooked dinner that evening, hamburgers from the grill on English muffins with a garlicky cilantro catsup and, from the garden, zucchini and a salad of mustard greens and cherry tomatoes. Her meals are usually meatless and more elaborate, but Dom had put in a special request. Marie is no big meat fan either, but whatever her vegan pals down at the health-food store tell her, she wants to make sure the kids get enough protein. When it’s my turn to cook, we often have pasta, fish, curry, or baked potatoes with the works.

We ate on the screen porch behind the house. It had briefly rained, but the sun came out again before setting, lifting mist from the fields and turning the hills a golden green. Insects and barn swallows darted through the slanting light. The cats hung around outside the screen hoping for handouts but not holding their breaths nor stooping to beg.

“When is school?” Dominic asked. He’s a handsome boy, with a round face and straight dark hair that give him an almost Eskimo cast, and he looks at you directly when he speaks, his brown eyes slightly narrowed as if every word were important.

“Two weeks,” Erica said.

Jasmine slopped more of Erica’s catsup on her burger and took a bite. “Do I get Mr. Huff?”

“I already had him,” Dom said.

“He’s doing second grade this year,” Marie said. “Mr. Clark’s doing first, and Ms. Tsavros is doing third.”

I waggled my eyebrows at Dom. “Lucky you. The lovely Miss Lu.”

Erica shot me a glance; neither Dom nor his teacher needed me cracking jokes about her. But he wasn’t listening, he was looking out off the porch.

“Tiffy got a bird.”

The ginger tabby was crouched over something in the ferns by the barn. One wing fluttered for a moment; she slapped it down with a paw.

Jas jumped up. “Save it!”

I put my arm around her. “Too late, sweetheart. Even if we got it away from her it would be crippled and die anyway.”

The bird gave out a plaintive half cry. “But it’s hurting.”

I pulled Jas onto my lap. “Sometimes there are things you can’t do anything about.”

Dom took the English muffin’s top off his burger and poked at the meat with a finger. The other cat, a black-and-white male, watched him intently from outside the screen.

After dinner, Erica and Marie and the kids played Snakes and Ladders. I washed the dishes then sat down on the red braided rug with them.

“Only four can play,” Dominic said.

“Meanies.”

“You can play the winners,” Jas said.

I took my glass of wine out onto the porch to watch the last of the day disappear from the sky. Dark shapes skittered by in the graying air; the birds had gone to bed, and the bats were bobbing for breakfast.

An hour or so later Erica took the kids upstairs to put them to bed and read them a story. I tuned the radio to the jazz station and picked up my book.

I dozed off after a while, and when I woke up, Thelonious Monk was plinking out “Straight, No Chaser,” and no one else was around. When the song ended, I turned off the radio and took my book upstairs. Erica and Marie were already in bed—on their stomachs, propped up on their elbows, heads together—doing a crossword. I undressed, brushed my teeth, and got in next to Marie.

When Marie first started sleeping with us, she’d taken the middle spot in the bed. “I’m trying to come between you,” she’d said.

Erica said I was “tired of the same old wife.”

“And you’re tired of men,” I’d said.

I think the truth of the matter lay in habit. I’d always slept on the right side of the bed, Erica on the left. Marie hadn’t changed that.

I caressed Marie’s pale, wiry back. Her black hair hung straight down, obscuring the sides of her face. I kneaded her neck and shoulders.

“Roundworm,” she said, “eight letters, starts with N, second to last letter D.”

I caressed some more. “Nude dude.”

Marie chewed her pencil. I reached across her to Erica’s back, dark-brown and muscular, with reddish highlights thanks to a Cherokee man who, according to family legend, would slip into the slave quarters at night to visit Erica’s great-great-great-grandmother. She rolled her shoulders. I slid my hand down to the small of her back and its deep spinal groove.

“Little higher,” she said. “Higher…to the left…scratch right there…ooo, perfect. I know, something toad, wormatoad, nematode.” Marie wrote it in. “So what does that give us now for nineteen-down?”

My ninth-grade English teacher once assigned the class an essay on The Ideal Family. What the teacher expected, and what the other kids delivered, was Dad goes to work in a suit and tie then comes home and changes into jeans to roughhouse with the kids, Mom works part-time with a women’s organization and cooks healthy meals, Timmy and Tammy help with the recycling and do their homework before watching TV.

My family life was nothing like that. Dad was away most of the time, supposedly on business—meetings, traveling from office to office, all a bit vague. He had a mailing address and phone number in Kansas City—his HQ, he called it. Mom referred to it as his “hindquarters.”

Mom worked, and had a lot of friends, mostly women, mostly divorced. A couple of evenings a week, three or four or five of them would hang out at our place, drinking wine and talking. Around six or seven o’clock, Mom would make dinner—spaghetti, often—or her friends would bring food—pizza, potato or macaroni salads—and we’d all eat together. Her friends were funny and seemed to like me. Nights when no friends came over, I’d try to entertain her or keep her company, at least when I was little. Not that she ever complained about being alone, but it always made me sad for her.

These women had common gripes: men did little of the housework or raising of kids, were away too much, hardly ever talked to their wives, and when they did, the most idiotic garbage spewed forth. Much of this had been true in my house before Dad left, as best I could remember, and I could see it in friends’ homes. I took it as fact, as an everybody-knows. So when the teacher asked us to write about The Ideal Family, it seemed perfectly logical to me that she wanted us to rethink the institution of marriage.

So I did. Men are needed to conceive children and help make money, but what they like to do is travel and hang out with their buddies. Women are needed to bear and raise children, and they like to be at home with their friends. Solution: the household should be composed of two or more women who help each other with the kids and keep each other company, and one man who’s free to roam as long as he sends money and occasionally fathers a child. I imagined smart, pretty women at home, glad to see me when I was there, not missing me when I was away. That was the kind of family I wanted.

I got a B+ for my essay and a comment that it was imaginative but highly impractical. Impractical how? What crucial piece of logistics had I overlooked? I was not asked, as were some of the others, to read my essay to the class. It didn’t occur to me until years afterwards that the essay might have had something to do with my being called in a day or two later by the school psychologist and asked gentle questions about how I was doing and if things were all right at home.

When Erica and Marie finished the crossword, I closed my book and switched off the bedside lamp. Moonlight was coming through high cloud, and a breeze stirred the curtain. I kissed Marie, stroked her belly, and found Erica’s hand already there. We shared a three-way kiss, a sweet confusion of faces, limbs, and torsos, and made love to the singing of frogs and crickets.

☽

In the morning, my rep called to ask if I wanted another job. Yes. Without work, without a small waiting list of jobs, I get restless. You’ve probably seen my stuff in magazines. Close-ups, often of inanimate objects—a wet razor with a tiny drop of blood on it, a coffee-cup ring on a wedding photo, a pair of sunglasses with a greasy thumbprint on one lens, a crumpled hundred-dollar bill stuck with chewing gum to the sole of an old sneaker. I’m known as the guy to call for a close-up with an edgy, off-kilter feel.

The job that put me in demand was half a face. The model’s mascara was clumped on her lashes, the off-color eye shadow was smudged, her lipstick was crooked, and a trace of it showed on the tip of a tooth. She wore no foundation makeup, and you could see every pore—the tiniest, daintiest, most Byzantinely mosaicked pores in the whole world. Her backlit wisp of a sideburn was of the finest, softest peach fuzz. The small wrinkles at the corner of her eye, on the bridge of her nose, and on her forehead weren’t the wrinkles of age but of youth, of post-adolescent tensions and stresses that each generation likes to imagine are unique to itself. The small scar high on her cheekbone made you wonder how she got it, how much it must have hurt—was a man involved?

It was a half face you wanted to love though it said it didn’t need love, a half face you wanted to take care of though it radiated do-or-die independence. It was the half face that launched forty million bars of soap in two months. The caption, which started as an ad slogan and became a trendy putdown, was “Lose the makeup.”

The new job my rep was calling about was condoms. He was talking beaches, sunsets, romantic couples, while I was already picturing a used rubber lying on the floor next to a Chinese takeout carton and a bottle of champagne. Or a Liza Minnelli CD and a whip, a Jane Austen novel and a gun. Condom chic: “Whoever you are, whoever you’re with, better safe than lonely.”

Marie came home from her job at the health-food store shortly after noon with veggie wraps. She fished them out of the bag with her long fingers and put them on a plate.

Erica came down from her office. “That your pay envelope for the week, honey?” Marie threw her the old-joke, not-funny-anymore look.

Dom mixed up some wasabi to go with the rolls. “Bet I can eat more of this than you.” When he first came here, we turned hot sauce into a game, which I let him win; soon he was beating me fair and square.

“No contest,” I said.

Once we sat down, he grabbed a bottle of juice and, his face contorting with effort, twisted off the cap. Jasmine wasn’t having any luck with hers, and Dom took it from her to open. His elbow hit his own bottle. I watched helplessly as it slid off the table.

About a foot from the floor, it was in Marie’s hand. She jinked the bottle to the left, and most of the small splash following it down dove through the mouth to rejoin its friends. Without admonition or reproof, she handed the bottle to Dom as he gave Jas her open one.

“How’d you do that?” I asked.

“No how, that’s how.”

When we’d eaten, Erica kissed Marie and thanked her for lunch. Jasmine did the same, and so did I. Dominic didn’t, but he also didn’t struggle very hard when Marie grabbed and kissed him.

After lunch I drove Dom to the dentist. When he’d last had his teeth cleaned, the dentist had found a cavity in a baby molar.

“Do I have to? It’ll fall out anyway.” We’d had this conversation before.

“But it’ll hurt until it does.”

“This’ll hurt too.”

“A little, and not for long.”

“Will I cry?”

“Any kid might. You probably won’t.”

I’d never seen him cry from frustration or anger, only out of physical pain, and it embarrassed him, more so in front of Marie or Erica than just with me.

“Will there be blood?”

“No.”

He seemed a little disappointed.

I stayed with him while the dentist worked, and Dom didn’t cry. The closest he came was during the Novocain shot, his face expressing the betrayal of being blindsided by a small, sharp, stinging pain rather than a big heroic one.

I patted his knee. “Worst part’s over.”

I took him to the store on the way home and told him he could get whatever he wanted. He and another little boy rummaged through the freezer together, discussing favorites and options, before both choosing Ben & Jerry’s Peace Pops.

“I’m going to my friend’s house,” Dom told the boy. “Want to come?”

How intensely Dominic and Jasmine go about making friends, and like most children, how quickly they do it. Not that it’s always easy for them. When excluded or rejected, she cries, begs, appeases; he gets mad or picks a fight. Making friends is a natural imperative for children, like eating and sleeping, but one which disappears, thymus-like, with adulthood.

Like the autistic who can’t intuit the emotions of others but has to look at the face, see the upturned corners of the mouth, the exposed teeth, the relaxed, crinkled look around the eyes, then put it all together and conclude: happy—I no longer seem to understand the body English, the sign language, the ritual of making friends. The man who doesn’t wish to dominate others—or perhaps can’t, but refuses to submit to another’s dominance—becomes a loner, the human equivalent of the rogue elephant or lone wolf. A romantic way, I suppose, of rationalizing one’s social failings.

The other boy checked with his mother, a pretty woman whose Land’s End gentrification seemed to have scrubbed her clean of any stain of sexuality.

“Kevin would love to,” she said, “but we don’t have time. We’ve been up visiting relatives, and now we’re on our way back to Connecticut.”

“Flatlanders,” Dom said when we were in the car. I laughed and ruffled his hair. Here only a year, and already he was using the local epithet for out-of-staters.

☽

Erica and Marie left to take the kids to their friends’ house and to shop for food. I went to my studio to sketch some possible condom shots. An hour or so later, I heard a car pull into the drive, a sports car from the snarly exhaust. I looked out the window.

A man got out of a rusty yellow Fiat convertible. He was lean, neither tall nor short, with dark curly hair. Instead of making for the front door, he looked out, away from the house for a few seconds, at the barn, then at the neighbor’s horses grazing in our field a hundred yards away.

When he turned toward the house, I got my first look at his face: high forehead, straight nose, strong jaw dark with beard shadow—handsome. As he gave the house the once-over, his manner showed none of the tentativeness of a stranger on someone else’s property. His glance was almost proprietary. He looked off down the drive then stepped up onto the front porch. I headed downstairs.

When I opened the door, he looked me up and down, cocked his head an inch to the right and smiled for just a moment. His eyes were a pale, bright gray.

“Aldo Zoria?” he asked.

“Yes.”

He glanced around the yard again, then turned to me and held out his hand—not so much out of social convention, it seemed, as from just then having made up his mind to do so. His grip was firm, warm, dry, and longer than perfunctory.

“Jonah Berthoud.” In the crystalline moment, only those two words moved. He pronounced it “bare-toe” rather than “burr-too,” as Marie did.

“Christ. Come on in.”

He swung out an arm, taking in the porch, the barn and field. “Why don’t we stay out here?”

From his even tone, I couldn’t tell if he was being contrary or simply felt like enjoying the summer afternoon. I offered him a wicker chair on the porch. Instead, he pulled a straight-backed wooden one to a sunny spot; I sat in the wicker.

He said nothing, and I wasn’t going to let his silence strong-arm me into opening a conversation whose direction, by all evidence, he would change in any case. After all, he’d shown up here at my door.

He resumed his slow inventory of the place. His eyes hesitated for a moment at the life-size faux-Roman marble bust staring at us impassively out the shed window from its perch on the workbench, but he didn’t smile or comment, as most people do, and his gaze passed on. After a minute or two, he turned his face up to the sun, eyes closed, as if alone on his own porch. Minky, the black and white cat, stepped silently up onto the porch and rubbed against Jonah’s leg. Jonah scratched Minky’s head with two fingers. Minky pushed into them and started to purr.

I heard the station wagon coming up the drive. It topped the rise and stopped at its usual place by the barn. Erica and Marie got out. Jonah watched but didn’t stand up. Erica opened the back of the car. Marie came straight to the porch.

“Jonah.”

He got up and stepped off the porch. She hugged him for a moment then broke it off. No kiss. Erica walked up with two bags in her arms and a questioning smile on her face.

“Erica,” Marie said, “this is Jonah, my husband.”